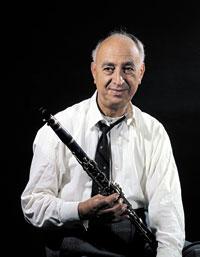

Mezz Mezzrow (November 22, 1899 - December 27, 1981)

Milton "Mezz" Mezzrow was born to Jewish, middle class parents in Chicago in 1899. He learned to play the saxophone in the reformatory school he landed in at the age of 16 after lifting a car with some friends. The Potomac Reformatory was also where he became acquainted with Jim Crow and Negro blues. Playing music in Chicago clubs after his release, Mezzrow was introduced to "tea" (marijuana) and also "hop" (opium). His 1946 autobiography Really the Blues, cowritten with Barnard Wolfe, draws a definite distinction between the two.

Milton "Mezz" Mezzrow was born to Jewish, middle class parents in Chicago in 1899. He learned to play the saxophone in the reformatory school he landed in at the age of 16 after lifting a car with some friends. The Potomac Reformatory was also where he became acquainted with Jim Crow and Negro blues. Playing music in Chicago clubs after his release, Mezzrow was introduced to "tea" (marijuana) and also "hop" (opium). His 1946 autobiography Really the Blues, cowritten with Barnard Wolfe, draws a definite distinction between the two.

Mounting the bandstand after his first stick of tea, Mezzrow writes,

"The first thing I noticed was that I began to hear my saxophone as though it was inside my head…Then I began to feel the vibrations of the reed much more pronounced against my lip…I found I was slurring much better and putting just the right feeling into my phases--I was really coming on. All the notes came easing out of my horn like they'd already been made up, greased and stuffed into the bell, so all I had to do was blow a little and send them on their way, one right after the other, never missing, never behind time, all without an ounce of effort. . . I began to feel happy and sure of myself. With my loaded horn I could take all the fist-swinging, evil things in the world and bring them together in perfect harmony, spreading peace and joy and relaxation to all the keyed-up and punchy people everywhere. I began to preach my millenniums on my horn, leading all the sinners to glory."

Mezz, "a sociable type," befriended and played with the likes of Bix Beiderbecke and VIPs Bessie Smith and VIP Louis Armstrong. He says he smoked weed with many of his musician friends, but does not name them in the book. Mezz mentored VIP Gene Krupa, teaching him to tune his drums like Louis's drummers; talked Fats Waller into playing blues just before Fats cut "Ain't Misbehaving"; did some arranging for Louis and convinced him to tour Europe, where he was a huge hit. In Paris, Mezz taught jazz to concert musicians who knew no Jim Crow prejudice.

Mezzrow ended up in New York in 1939 where he was responsible for spreading Armstrong's tunes to jukeboxes all over Harlem. Word soon spread that the white boy had the best golden leaf "muta," due to Mezz's Mexican connection, and he started selling it to his many friends, at a time when a Prince Albert can full cost $2. In Really the Blues the authors offer a jive-speak interaction with several customers, translated in the Appendix into boring old English. It begins,

FIRST CAT: Hey there, Poppa Mezz, is you anywhere?

ME: Man I'm down with it, stickin' like a honky.

FIRST CAT: Lay a trey on me, old man.

ME: Got to do it, slot.

Mezzrow was soon more famous for his marijuana than for his playing. Mezz, or the Mighty Mezz, became synonymous with good weed or anything good, the Phat of its day. Cab Calloway's Hipster's Dictionary defines mezz as "anything supreme, genuine." The Stuff Smith song, "If You're a Viper," starts out:

Dreamed about a reefer five foot long

The mighty mezz, but not too strong,

You'll be high but not for long

If you're a Viper.

Mezz describes "acres of marijuana" being smoked at the Lafayette Theatre in Harlem, with performers lighting up as well as the audience. The kids in Harlem dressed sharp like Louis and Mezz, and the slogan in their circle of Vipers was, "Light up and be somebody." Mezz wrote,

Mezz describes "acres of marijuana" being smoked at the Lafayette Theatre in Harlem, with performers lighting up as well as the audience. The kids in Harlem dressed sharp like Louis and Mezz, and the slogan in their circle of Vipers was, "Light up and be somebody." Mezz wrote,

"Us vipers began to know that we had a gang of things in common…We were on another plane in another sphere compared to the musicians who were bottle babies, always hitting the jug and then coming up brawling after they got loaded. We like things to be easy and relaxed, mellow and mild, not loud or loutish, and the scowling chin-out tension of the lushhounds with their false courage didn't appeal to us. Besides, the lushies didn't even play good music--their tones came hard and evil, not natural, soft and soulful…We members of the viper school were for making music that was real foxy, all lit up with inspiration and her mammy."

Mezzrow soon attracted the attention of New York racketeers, who pressured him to expand his business and cut him in. But neither Mezz nor his supplier were interested in going big time. Mezz writes, "Soon I was getting visits from Dutch Schultz's boys and Vincent 'Babyface' Coll's boys every day in the week. With each day they got less good-natured about it. Each day their voices got harder, and their demands more insistent."

Soon some old friends started asking Mezzrow, who was not longer using opium, to get them some "hop." He made a connection and was quickly hooked again for two years, losing many opportunities to play and advance his career. He eventually started one of the first integrated jazz orchestras and had success with some Parisian recordings he had made with Hugues Panassie.

In 1940 Mezzrow was arrested at Flushing Meadows, Long Island carrying 40 joints (only 30 of which made it to court for evidence). A lieutenant from the narcotics squad tried unsuccessfully to get Mezz to stool on other Harlem pot peddlers, and he was sentenced to 1-3 years in Rikers Island.

After noticing that some inmates from Rikers and Hart Island were being shipped to King's County Hospital and being given all the reefer they wanted to smoke so that doctors could study its effects, Mezz wrote a legal writ and got a release hearing in the summer of 1942. He argued that he was being held for a substance doctors couldn't find was harmful, and was told by the judge, "The only trouble is, if I let you go you'll get right out with all the rest of your people and re-elect Roosevelt."

Really the Blues was named by fellow clarinetist Woody Allen in 2011 as one of his five most influential books.