China, the U.S., and Drug Policy

By Ellen Komp 2008

The U.S.’s desire to open trade with China brought about national and international laws banning drugs. Now, one hundred years later, the United Nations is finally considering the human rights impacts of drug laws.

Journalist Jill Jonnes helped create the US Drug Enforcement Agency museum and published the 1996 book Hep-cats, Narcs, and Pipe-Dreams: A History of America's Romance with Illegal Drugs with a National Endowment for the Humanities fellowship. In her book, she writes, "Oddly enough, it was not the states or the national reform movements that launched the fight for federal antidrug laws and pushed them through. Instead, it was the U.S. State Department. Why ever for? one might well ask. Initially, the State Department's surprising interest in drugs had everything to do with designs on the vast China market and currying favor."

Journalist Jill Jonnes helped create the US Drug Enforcement Agency museum and published the 1996 book Hep-cats, Narcs, and Pipe-Dreams: A History of America's Romance with Illegal Drugs with a National Endowment for the Humanities fellowship. In her book, she writes, "Oddly enough, it was not the states or the national reform movements that launched the fight for federal antidrug laws and pushed them through. Instead, it was the U.S. State Department. Why ever for? one might well ask. Initially, the State Department's surprising interest in drugs had everything to do with designs on the vast China market and currying favor."

It's been well documented that the British forced China to accept opium from its Indian colonies in order to restore balance of trade with its tea-producing partner, which also supplied silk and other sought-after manufactured goods. Alarmed by the number of opium addicts in the country by 1830, Chinese official Lin Tse-hsu wrote a letter to Queen Victoria pointing out that her country ought not to export a product that Britain herself had made illegal. England refused to stop the exports.

After Chinese ships tried to turn back English merchant vessels in November 1839, England sent war ships and troops, starting the first of two Opium Wars (1839-42 and 1856-60), the second of which ended with a Scottish descendant of Robert the Bruce burning the Chinese emperor's Summer Palace, the inspiration for Coleridge's Xanadu of Kubla Khan. The resulting open-door Treaty of Nanking was highly favorable to the victorious English, and after it opium imports into China tripled.

The Spanish-American War of 1898 made the United States a colonial power in Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines. Future President William Howard Taft, a man so obese he had to have a bathtub specially made for him, studied the opium problem in the Philippines, and "decided the whole issue presented a great opportunity for the United States in the Far East, especially in China," writes Jonnes, who added, "American businessmen had been eyeing the Chinese multitudes hungrily for years, but the British and the Europeans dominated the scene. Now American businessmen and reformers saw a natural opportunity to advance their respective causes by actively supporting China's desire to end all opium imports.” So as the British had conquered the East by pushing an addiction on them, the U.S. would do so by fighting that same addiction.

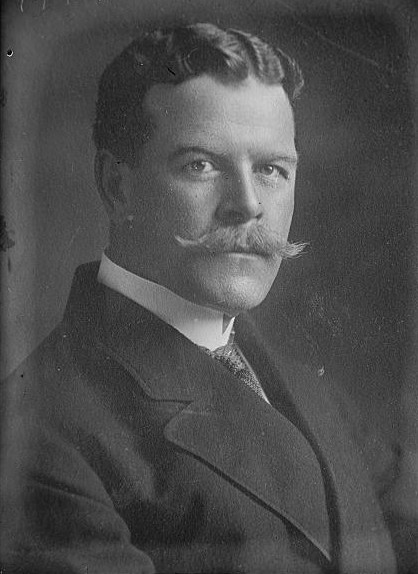

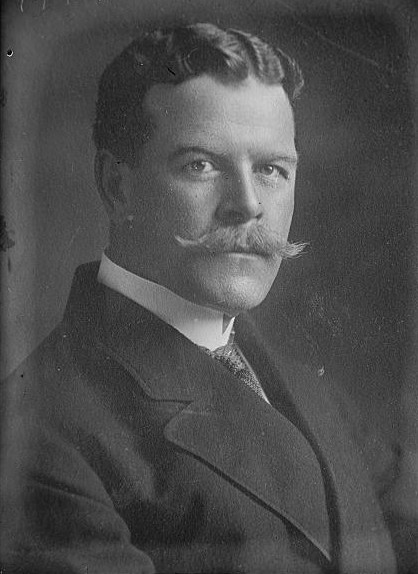

The State Department proposed an international conference in Shanghai to tackle the issue. The problem was, the U.S. didn't have its own house in order. Dr. Hamilton Wright, an M.D. (pictured left) who made his name by finding a pathogen that "caused" beri-beri (before it was discovered to be a vitamin deficiency), was appointed as U.S. Representative of the International Opium Commission and set about to pass domestic legislation banning addictive drugs. Wright became the first of many U.S. propagandists of the war on drugs. "Of all the nations of the world, the United States consumes most habit-forming drugs per capita," Wright said in 1911, calling opium "the most pernicious drug known to humanity."

The State Department proposed an international conference in Shanghai to tackle the issue. The problem was, the U.S. didn't have its own house in order. Dr. Hamilton Wright, an M.D. (pictured left) who made his name by finding a pathogen that "caused" beri-beri (before it was discovered to be a vitamin deficiency), was appointed as U.S. Representative of the International Opium Commission and set about to pass domestic legislation banning addictive drugs. Wright became the first of many U.S. propagandists of the war on drugs. "Of all the nations of the world, the United States consumes most habit-forming drugs per capita," Wright said in 1911, calling opium "the most pernicious drug known to humanity."

Wright's initial attempts to pass legislation met with resistance from druggists and doctors, who insisted cannabis be removed due to its medical uses. Next year will mark the 100th anniversary of the 1909 Opium Exclusion Act forbidding importation of smoking opium, which was passed to show that the U.S. was serious about the Shanghai Convention. In 1914 the Harrison Narcotics Act passed, forbidding doctors to prescribe to “addicts,” and the underworld moved in. Not long afterwards, as the DEA museum demonstrates, tincture bottles were replaced with submachine guns.

This year, the United Nations' target date for "eliminating or reducing significantly" the illicit cultivation of cannabis, coca and opium, the UN heard testimony for the first time from NGOs like the ACLU and NORML (National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws), resulting in a declaration and resolutions that emphasize the need to incorporate human rights into drug policy. These documents will be presented to the UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs at the UN General Assembly Special Session on Narcotic Drugs in Vienna in March 2009 as they debate their next 10-year strategy.

It's a good first step towards righting the wrongs that happened long ago, and have caused so much misery in their wake.

You can read the NGOs declaration and resolutions here: http://www.vngoc.org/images/uploads/file/BEYOND%202008%20DECLARATION%20AND%20RESOLUTIONS%20FINAL(1).pdf

Also see http://www.canorml.org/news/UN-Vancouver_Relse.htm and http://www.aclu.org/drugpolicy/gen/35894prs20080707.html

Journalist Jill Jonnes helped create the US Drug Enforcement Agency museum and published the 1996 book Hep-cats, Narcs, and Pipe-Dreams: A History of America's Romance with Illegal Drugs with a National Endowment for the Humanities fellowship. In her book, she writes, "Oddly enough, it was not the states or the national reform movements that launched the fight for federal antidrug laws and pushed them through. Instead, it was the U.S. State Department. Why ever for? one might well ask. Initially, the State Department's surprising interest in drugs had everything to do with designs on the vast China market and currying favor."

Journalist Jill Jonnes helped create the US Drug Enforcement Agency museum and published the 1996 book Hep-cats, Narcs, and Pipe-Dreams: A History of America's Romance with Illegal Drugs with a National Endowment for the Humanities fellowship. In her book, she writes, "Oddly enough, it was not the states or the national reform movements that launched the fight for federal antidrug laws and pushed them through. Instead, it was the U.S. State Department. Why ever for? one might well ask. Initially, the State Department's surprising interest in drugs had everything to do with designs on the vast China market and currying favor." The State Department proposed an international conference in Shanghai to tackle the issue. The problem was, the U.S. didn't have its own house in order. Dr. Hamilton Wright, an M.D. (pictured left) who made his name by finding a pathogen that "caused" beri-beri (before it was discovered to be a vitamin deficiency), was appointed as U.S. Representative of the International Opium Commission and set about to pass domestic legislation banning addictive drugs. Wright became the first of many U.S. propagandists of the war on drugs. "Of all the nations of the world, the United States consumes most habit-forming drugs per capita," Wright said in 1911, calling opium "the most pernicious drug known to humanity."

The State Department proposed an international conference in Shanghai to tackle the issue. The problem was, the U.S. didn't have its own house in order. Dr. Hamilton Wright, an M.D. (pictured left) who made his name by finding a pathogen that "caused" beri-beri (before it was discovered to be a vitamin deficiency), was appointed as U.S. Representative of the International Opium Commission and set about to pass domestic legislation banning addictive drugs. Wright became the first of many U.S. propagandists of the war on drugs. "Of all the nations of the world, the United States consumes most habit-forming drugs per capita," Wright said in 1911, calling opium "the most pernicious drug known to humanity."